The Tragic Security Implemented in Building Management Systems

- tags

- #Security #IoT

- categories

- Authentication Security

- published

- reading time

- 5 minutes

This post dicusses building management systems (BMS), the (horrible) state of their security, and the security impact that these systems can have.

What are Building Management Systems?

BMS are computer-based control systems, installed in buildings to manage and monitor the mechanical and electrical equipment such as ventilation, lighting, power, and fire systems. They are installed in most new buildings (and many old ones), as they can automatically and manually be optimized for efficiency, and comfort. Essentially, a BMS functions as the brain of a building, ensuring systems (such as HVAC) operate together efficiently.

Why care about this?

Naturally, companies quickly realized that if they equipped such systems with network ethernet, they would enable customers to connect to the BMS remotely, allowing them to control a building’s systems remotely via a network protocol such as BACnet or LonTalk. Examples of these products include the Swegon Gold/SuperWise BMS controllers, which are commonly used in Nordic countries. Other examples include the Tridium Jace controllers which run Niagra - with this sort of system primarily being used in the USA.

The issue

The problem, however, is that many of these systems are woefully insecure. So much so, in-fact, that one does not need to do anything more than search up the default username and password in google!

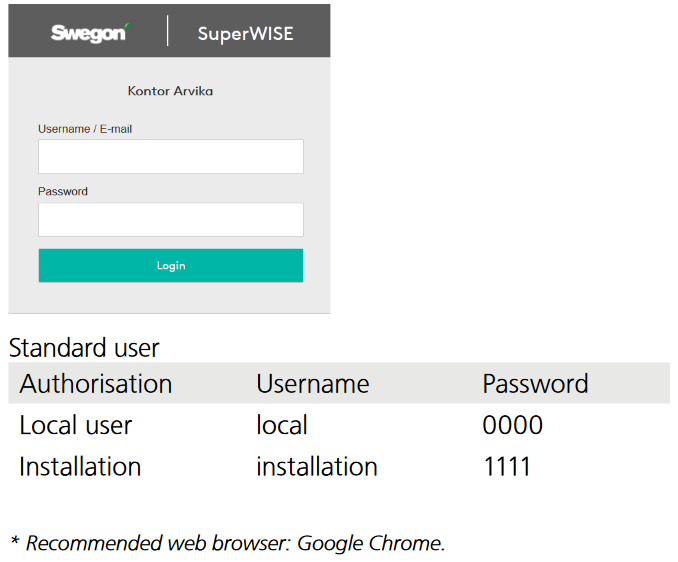

If we, for example, decide to search up the very complex and evolved search string of swegon superwise password, we can open the first result, search for the password, and have it helpfully shown:

Whilst, in theory, this is not an issue if the user is forced to changed the default credentials upon device setup, sadly that is not the case.

In regards to Tridium/Niagara devices, the security is somewhat better. Due to the fact that the software was licensed out to a large number of other manufacturers, the default password on these devices varies. Furthermore, the issue of default credentials and other vulnerabilities being present has already being known for a long while (see for example this NIST CVE, this POC, or this FBI warning), and thus some manufacturers have issued updated forcing users to change the default credentials. However, many manufacturers haven’t, and of those that have, few customers have updated the firmware of their systems. With a bit of online sleuthing on forums such as on hvac-talk.com (seriously, this is a great forum for finding all sorts of info on HVAC and BMS systems), passwords can be found.

The Impact

So how large is the impact of these? Well, running simple searches on sites such as Shodan or Criminal IP reveals a lot of results. In the case of Swegon devices, these results will, alarmingly, often lead to controllers in modern/new buildings, many of which are of very large/public nature.

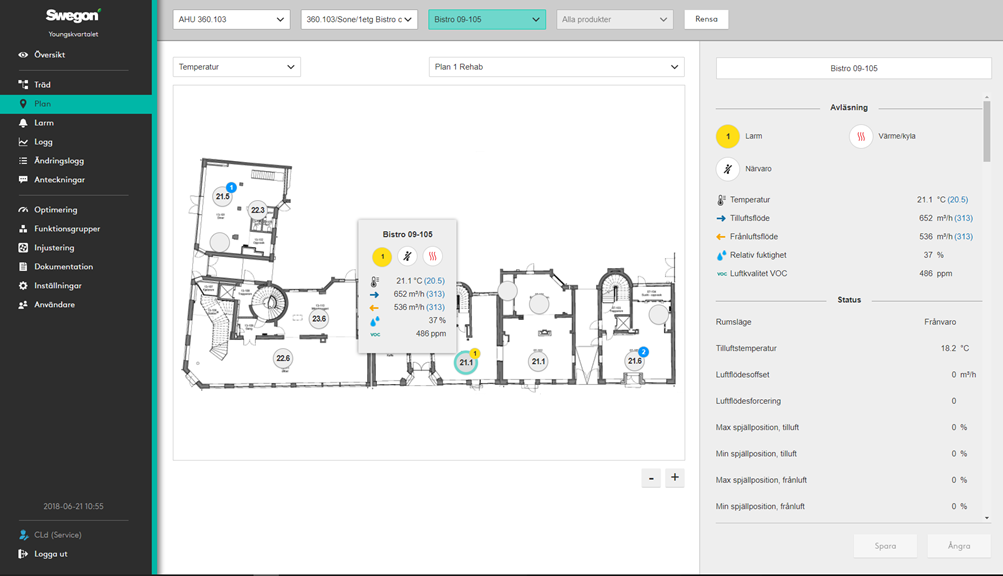

Once logged in, any ill-meaning party will be greeted by a UI which allows them to do any number of things. These include getting access to the blueprints/plans of the building (as they are often used when mapping the different systems in a building), statistics and real-time information on information ranging from room occupancy, to energy usage and ventilation fan speed(s).

With the ability to supress/raise alarms, or perhaps inject malicious code via the UI to a system in the building via Scada or a similar protocol, an attack could cause all sorts of issues, not least being the possibility for causing panic within the building (if e.g. a fire alarm or sprinkler system was triggered). Alternatively, with the ability to schedule events, an attack could for example set up a schedule which makes all systems run at 100% overnight, generating an expensive power bill, and increased wear on systems in the long-term (for example such as was done with Stuxnet).

Naturally, the UI also allows users to update the BMS firmware by uploading a zip folder with the update code! However, it’s worth noting that I have not been able to find the firmware on the internet. Since the BMS is still around 120-300 euros on ebay, please reach out to me if you for some reason have one you’d be willing for me to look at! I’d love to take a look at the hardware side of the device.

In regards to Tridium devices, they’re used for a massive range of different purposes, so the impact of their default passwords being known depends truly on the target.

Final Thoughts

One of the main questions I’ve been asking myself for a while is - why aren’t more (if not all) of these systems causing huge security issues which pop-up into the news? I think the answer is partly due to the fact that it’s difficult (in particular with Tridium devices) to identify and search for precise targets, with many such controllers being exposed via IP addresses which simply lead back to internet service providers with ICANN searches. It makes it both challenging for white-hat hackers to report such systems, and for black-hats to identify systems of interest.

However, I think a lot of these systems are in actuality being exploited, but without their origins being dectected. Indeed, there is evidence for such attack in the past, for example the time a Las Vegas casino had its high-roller database stolen through a fishtank thermometer.

I also think it’s important to note that attackers may, instead of using the access to tamper with buildings and gain information, use the devices in bot-nets, or as proxies, which represents (arguably) a greater collective issue than a few rogue sprinklers…